What did you discover or learn during the process of on-site testing?

Ui: I learned a lot from the Lab about designing on-site tests—particularly the standards used for evaluation. I was grateful that the Lab went as far as to measure the detection accuracy of our product and figure out an evaluation method that caregivers would be happy with given the way it was measuring. Development companies tend to be heavy-handed, which can be hard on users—but the Lab was able to strike a delicate balance between the two on that tricky point. Thanks to the experience of the Lab team, I realized that if you’re thinking about developing a product, you’ll get the best result by relying on professionals to get you there.

Haga: Every nursing care organization has their own approach to excretion care and assessment, so we wanted to do our on-site evaluations in a way that would allow as many of them as possible to use the technology. I’ve personally visited over 150 nursing care facilities run by other companies from Hokkaido to Okinawa, and Ms. Ui’s been involved with many organizations as well. By regularly discussing and exchanging feedback on a variety of issues, we decided that we wanted to incorporate technology in a way that reflected the state of the industry as a whole—not just excretion assessment—and gave people solutions that didn’t rely solely on the expertise and knowledge of their staff. The fact that we shared this conviction was incredibly encouraging.

Kondo: I’m incredibly grateful to Ms. Ui and her team for the sincere approach they took to collecting user requests throughout the on-site testing and evaluation process. I also realized how important it is that the testing side have a proper understanding of the purpose of the device. It’s only after people know what tools are for and how to use them that they deliver the intended results. And once people start using a device, they start wanting it to do even more than it’s designed to do, which makes them dissatisfied with it and wanting a different one. The experience reminded me that because tools are simply tools, human intelligence is increasingly important the more useful to us they become.

Where is Helppad now, and what are your hopes for it in the future?

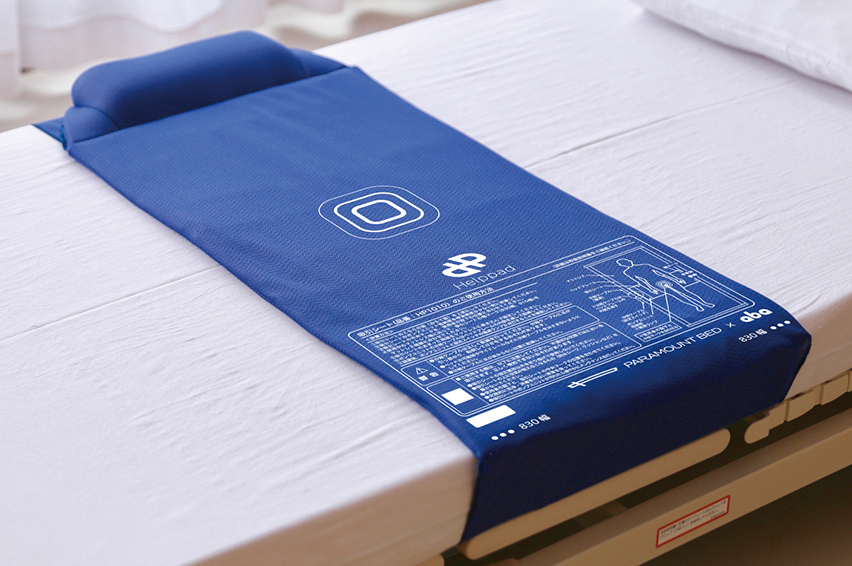

Ui: We’ve already delivered a total of around a hundred devices to about eighty nursing care facilities, including those that we interviewed, that helped with on-site testing, and purchased them. And we’ve heard from many more who want to purchase them once their nursing care robot subsidy comes through. Going forward, we want to make the Helppad into a device that people “don’t even know it is there.” We have a few ideas about how to do this, including micro-sizing it and building it into diapers or cloth underwear, or even making it into a kind of in-room installation that you’d just set up somewhere and leave alone. Either way, we want our basic concept to remain unchanged. We’ll always remember our promise to caregivers on the front lines: caregiving is meant to support people’s lives, so it shouldn’t compromise their lives.

Haga: We’re currently running on-site evaluations at two Sompo Care facilities, but we’re planning to expand and include those with more subjects that meet our requirement definitions. In the future, we hope to develop products that can be used by an even wider range of people, using methods that keep our current concept intact while placing as little burden as possible on users and caregivers alike. As Ms. Ui mentioned, if they can create a miniaturized or standalone product, it will allow the device to be used by more people and result in even higher-quality care. In addition, the Lab is always looking to get a better understanding of technology and more clearly define its aims and application methods so that we know where we should be relying on it, what we should be leaving to people, and how to divide it up. In this way, we hope to expand the fields in which care facilities can utilize technology instead of manpower alone.

Interviews based on information current as of September 2021.